Note from the CPD Blog Manager: This is part one of a two-part essay based on a talk, “Narratives, Propaganda and 'Smart' Power in the Ukraine Conflict,” that the author delivered at Johns Hopkins University, SAIS...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

Culture Posts: Propaganda by Default in Ukraine

Last week I joined several hundred other scholars at the 2014 International Studies Association convention. As expected, opinions on events in Ukraine abound. I was struck by the multiplicity of versions of the same events. More interesting still was how readily scholars were to label different versions as “propaganda.” This concerns me, especially in today’s communication ecology. Strategically, the default to “propaganda” creates blind spots, its own reverse deception, and most importantly, a lost opportunity.

Propaganda – Informational or Relational?

As a student of persuasion, I appreciate propaganda’s harm as a deliberate attempt to disguise or manipulate information for political gain. Even the garden-style variety of propaganda that flashes binary opposites at the masses can be potential destabilizing by polarizing publics: our good – their evil, out truths – their lies, our heroic patriotism – their unleashed nationalism; our righteous defense – their wanton aggression. The very simplicity of such binaries makes them highly contagious in the public sphere. Yet, their simplicity makes them readily detectible and hence diffusible.

More sophisticated levels of persuasion employ tactics that make the validity of information less apparent. The information may ring true, but the logic may not. Most of the mass media era tactics were captured in Yale University professor Leonard W. Doob’s classic 1950 study “Goebbels’ Principles of Propaganda.” Joseph Goebbels was the Nazi Minister of Propaganda. Some of the tactics have survived to the digital age. While digital technology and the anonymity of the online environment make it easier to distort and disseminate information, other digital advances and strategies such as crowdsourcing or data scrapping make information easier to detect.

However, focusing on information content to distinguish propaganda from public diplomacy may not be as helpful as it once was. From an information-based perspective, “objectivity” and “truth” are prime determinants of credibility and by extension, persuasion. However, from a relations-based perspective, relational affinity may be more powerful than neutral facts to determine credibility.

Many of the convention delegates talked about the credibility of the different news sources. They compared U.S. news outlets with Russia’s RT, Britain’s BBC or China’s CCTV. Not surprising, even for the purist, often “what is credible” (information) closely paralleled “who is credible” (relationship).

The problem is not the information per se, but how it’s interpreted. Even factual and credible information can be distorted not by others, but inadvertently by one’s self.

Which brings me to the problem inherent in human listening.

Listening through Filters

The problem even with the best listening is the assumption that somehow we are taking in information raw, or unfiltered as something distinct and separate from ourselves. If only that were possible.

Listening involves filters. We tend take in information, including information on the actions and statements of others, through the lens of our own knowledge and experience. We evaluate others accordingly. Yet, other humans tend to do what we do. They act based on their own knowledge and experience. If their experiences differ from our experiences, not only is their behavior likely to be different, so too are the motivations for that behavior.

If we impute intent for their behavior based on our experience and knowledge rather than theirs, our interpretation of their behavior is likely to be faulty. The wider the gap in experiences and perspectives, the more our interpretation is likely to err. The classic example is found from intelligence reports, with the classic example being the failure of U.S. and British intelligence to anticipate the revolution in Iran. The problem was in not gathering information. It is the interpretation of the information.

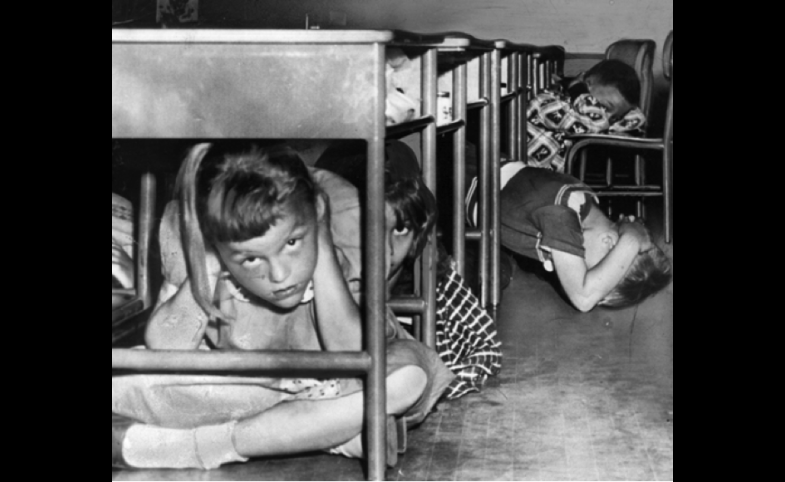

Not only is information interpreted through one’s filter of knowledge and experiences, those experiences may be charged with emotion. When I was in grade school we periodically had “duck and cover” drills for a nuclear attack by the Soviets. The alarm would sound unexpectedly and we would all scramble under or duck our desks and cover our heads. After a few minutes or so, having survived the nuclear attack, we would resume class never knowing when the next attack – or real attack – might come. Reflecting back on this experience it is not a neutral taking in of information. What purpose does such an exercise serve for a 7 year old except to cultivate an early fear of those would “nuke” you.

Emotions are a powerful filter in listening. CPD research fellow Sarah Graham is charting new PD territory by shining a spotlight on the overlooked role of emotions in public diplomacy. Such research is vital to understanding public diplomacy’s impact. Emotionally packed information can elude scrutiny. A shared emotional experience can foster a tacit agreement of what is common knowledge and even common sense. Who would question what “everyone” knows as true. Recognizing the propaganda of a feared enemy can be one of those shared truisms.

Which brings me to why PD scholars need to move beyond listening.

From Listening to Perspective Taking

In any type of public communication, including public diplomacy, it is absolutely critical to understand the public from the public’s perspective. Understanding the public’s perspective requires going beyond listening to perspective taking.

Listening is taking in information. Perspective-taking is understanding and interpreting information not from one’s own frame of reference but the audience’s.

Perspective-taking is especially critical when a public acts in unexpected or counter-intuitive ways. What may be dismissed as “propaganda,” may not be by the public. To further deride a public’s behavior as “irrational” or naïve to the propaganda is a missed opportunity of perspective taking. A savvy PD analyst explores all perspectives, especially the counter-intuitive ones.

Clearly, not all countries viewed Russia’s action as “propaganda.” For some, Russia’s actions were not only understandable but predictable. For others, they were even appealing. Again, for the savvy PD analyst, it is not whether that analyst finds the policies attractive, but whether the public appears to find them so. Such attraction might in another universe be referred to as Russia’s “soft power.” While the events may appear as a media flash point, they were not achieved overnight. A Chatam House’s report details Russia’s extensive PD activities well before the recent events. Yelena Ospiva, whose doctoral research on Russian soft power, provides insight into how Russia’s thinking and strategy manifest in Ukraine.

There is a desperate need for more comparative PD scholarship and practice, including new conceptual models of soft power. As Bruce Gregory and others have noted on more than one occasion, public diplomacy has been dominated by the U.S. experience and example. Whereas the U.S. perspective may be the dominant perspective in PD, the danger is it is not the whole perspective. If the PD field is to grow beyond the US public diplomacy experience and model, it needs to make room for exploring the practices of other countries without delegitimizing or dismissing them as propaganda.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

March 22

-

February 23

-

February 22

-

March 4

-

April 11

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.