In 1905 my club – Middlesbrough – broke the world transfer fee record when it paid Sunderland £1,000 to sign Alf Common. It was the first time in history a football player had been sold for four figures. Now, 112 years later, the record has been smashed for the second summer running, with Paris Saint-Germain paying £198m for Brazilian superstar Neymar, the highlight of the latest period of transfer hyperactivity that ended yesterday. This phenomenon transcends sport. How can an individual in any sphere be worth £198m? Who would pay that and why? What does the now normalised outlay of mind-boggling fees and salaries say about society? How did we get here?

This shattering of the world transfer record is clearly a pointed reminder that what was once the “people’s game” is no longer the preserve of most of the people who play or watch it. Steve Gibson, a north-east chemical transport magnate who bought Middlesbrough 30 years ago, is the last of a dying breed who used to dominate the upper echelons of the sport: a local businessman, born and brought up in the town where he owns the local football club (which, ironically again, broke its own transfer record this summer).

But after the inception of the Premier League in 1992, football began its demise as a socio-cultural institution, and set out on its trek to becoming a purely commercial proposition. This has resulted in the arrival of owners with little interest in their local communities – the club part of “football club”. Think of the Glazer family at Manchester United and the Fenway Sports Group at Liverpool. With them has come a North American ideology that has advocated free-market economics, overseas market entry and, dare I say it, profit.

Many football fans have been struggling to understand or accept an ideology that has, in their view, taken the game away from them and put it into the hands of people they often know little about and have little in common with. The effects of this have included the creation of Supporters Direct, a network that helps supporters gain influence in the running of their clubs, the Against Modern Football movement, and a general disaffection with what was once most people’s favourite game.

But this ideological transition is not yet over. Just as many fans have been grudgingly coming to terms with football’s new reality, Qatar Sports Investments shelled out the £198m to transfer Neymar from Barcelona. This hardly came as a surprise. Neymar is a phenomenal talent. But it is important to understand what lies behind this: governments from across Asia have been targeting football for some time as a means of building their global soft power and boosting their images.

This time last year, speculation was rife about which big-name player would next be heading east, after the Brazilian star Hulk’s move to China. He is one of many familiar names who have headed to the country’s Super League over the past two years. The reported £600,000-plus weekly salary Carlos Tevez attracted when he made the move to Shanghai prompted the ire of China’s government, but not before a flurry of similar transfers which inflated player values globally.

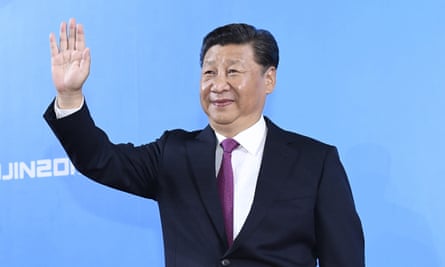

An interesting aspect of the Neymar frenzy was that most of us stopped talking about China and started talking about Qatar. It shouldn’t deflect from the fact that in the past two years China’s state institutions, investors and businesses have engaged in a spending spree aimed at delivering President Xi’s vision of the country winning the men’s World Cup by 2050. Huge sums of cash have been sunk into Atlético Madrid, Internazionale and several Fifa sponsorship deals. Even Northampton Town is now Chinese-owned.

It is a long way from China to Qatar, but the countries have a shared approach to football. They cast the sport as a means to an end, not an end in itself. Football remains the global game. Governments in Asia are acutely aware of this, and of football’s consequent power. They know that it can be a lever in their pursuit of other goals, such as nation-branding, soft-power projection and resource acquisition.

Qatar, which is controversially hosting the World Cup in 2022, has proved particularly adept at using football to make a positive global statement about itself and its ambitions. It should be no surprise that Neymar arrived in France shortly after the imposition of sanctions on Qatar by its Gulf neighbours, though whether Neymar’s signing and Qatar’s investment in sport will be an effective counter remains unclear.

China has a similar policy of “stadium diplomacy”. All four stadiums used at this year’s Africa Cup of Nations in Gabon were built free of charge, or through the provision of soft loans, by China. No coincidence then that Gabon, whose main export is crude oil, subsequently became a comprehensive trade cooperation partner with China.

This represents a new ideology of football – state-led, hugely political and lavishly resourced. It is the antithesis of both the European socio-cultural view of football and of North America’s free-market liberalism. The £198m Neymar deal symbolises the lengths to which Asian governments will go in seeking to achieve their broader goals.

If and when you see him in action for his new club this season, remember why he is there: a reflection of the European, North American and Asian ideologies fighting for territory.