It had all the trappings of a globally significant confab: big-deal appearances (by Google, BBC), a weighty theme ("the digital age"), and speechifying by international pooh-bahs. Rupert Murdoch, the CEO of News Corp., even delivered a peppery keynote, vowing war on "content kleptomaniacs." But despite its name, the World Media Summit was itself a media bust, especially in the English-speaking press, which barely covered the three-day event held last fall in Beijing's Great Hall of the People. The problem? The conference was a propagandafest, a "media Olympics" hosted by the Xinhua News Agency, an official organ of the Chinese Communist Party. If China has its way, however, ignoring Xinhua won't be an option for long.

For decades Xinhua has been an unavoidable presence in China. It has a monopoly on official news and the regulatory power to complicate life for other media outfits. But as China has grown in wealth and international stature, Beijing has tired of feeling overlooked or maligned by the Western press. So Xinhua's role has been redefined, as a means for China to wield soft power abroad. In the last year alone, the 80-year-old outlet launched a 24-hour English-language news station, colonized a skyscraper in New York's Times Square, and announced plans to expand its news-gathering operation from 120 to 200 overseas bureaus and as many as 6,000 journalists abroad. Not to be outdone by its Western peers, Xinhua has also released an iPhone app for "Xinhua news, cartoons, financial information and entertainment programs around the clock."

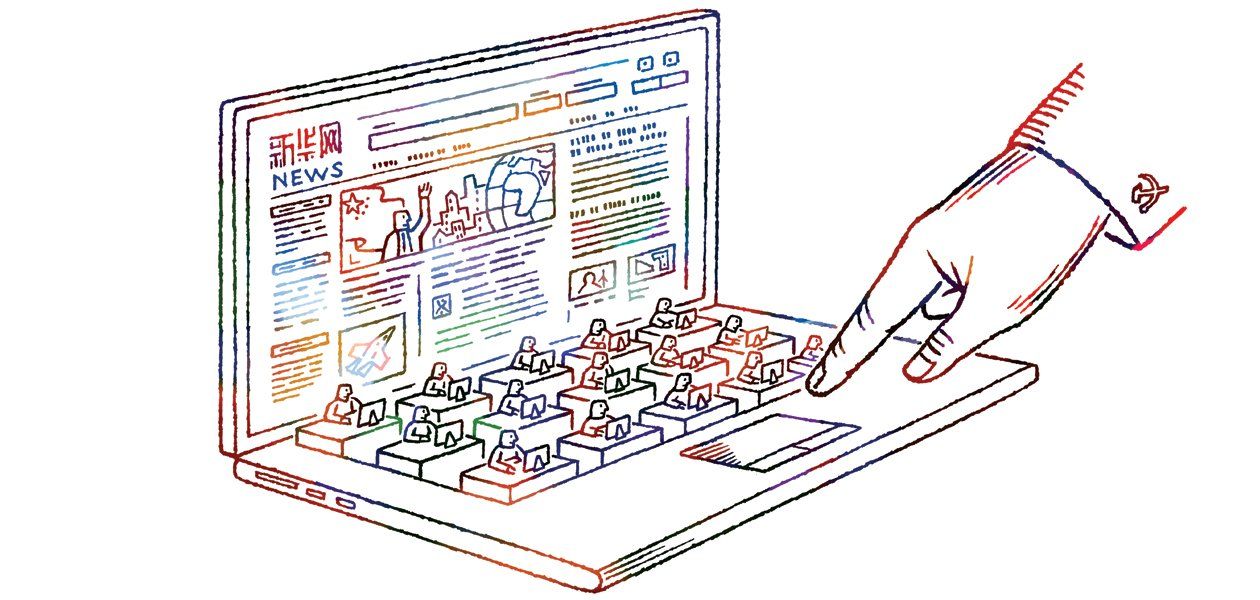

With a price tag estimated in the billions of dollars, the new Xinhua is an expensive megaphone. But it's key "to breaking the monopoly and verbal hegemony" of the West, according to remarks released last year by Xinhua's president, Li Congjun, who often sounds like he's channeling Noam Chomsky. Xinhua declined to make officials available for this story, citing "holiday season." But clearly the effort has to do with the new rules of propaganda, too. Where the game was once about suppressing news, it's now about overwhelming it, flooding the market with your own information. Airbrushing photos is for amateurs.

The challenge is finding an audience for "news" that is best known for its blind spots. The typical Xinhua sentence is thick on the tongue ("out of which 20 percent were the HIV-infected persons") and often inaccurate by design. In Xinhua's world, the Tiananmen Square massacre never happened, Falun Gong is an evil cult, and the Dalai Lama is the Guy Fawkes of Tibet. Xinhua also gathers sensitive news—such as the full heads-rolling horror of the Uighur riots last summer—and releases it to Chinese officials alone. It's as if The New York Times were to stamp its scoops "internal reference reports" and file them to President Obama.

Nevertheless, Xinhua may be the future of news for one big reason: cost. Most news organizations are in retreat, shuttering bureaus and laying off journalists. But the former "Red China News Agency" doesn't need to worry about the inconvenience of turning a profit. As a result, it might do for news what China's state-run factories have done for tawdry baubles and cheap clothes: take something that has become a commodity and foist it onto the world far more cheaply than anyone else can. "It gives them an inherent competitive advantage" says Tuna Amobi, a media analyst for Standard & Poor's, who thinks Xinhua's cheap news "might fly." A subscription to all Xinhua stories costs in the low five figures, compared with at least six figures for comparable access to the Associated Press, Reuters, or AFP. For customers who still can't afford the fees, a Xinhua aid program offers everything—content, equipment, and technical support—for free.

It's an alluring deal in the Middle East, Africa, and the developing world, where newsprint sales are up and there's hunger for non-Western perspectives. Xinhua operates in areas uncovered by the ratings agencies, so its hard to gauge audience size. But in recent months, Xinhua has signed content deals with state-run outlets in Cuba, Mongolia, Malaysia, Vietnam, Turkey, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe, making it a leading source of news for Africa and much of Asia, with more boots on the ground in those continents than any other organization. "They are literally everywhere," says Orville Schell, director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations at the Asia Society in New York.

It helps, of course, that Xinhua's spin diminishes when the news doesn't involve China. "I read them quite a lot," says Daniel Bettini, foreign editor for Yedioth Ahronoth, one of Israel's largest newspapers. Editors in Pakistan and Turkey also praise Xinhua, noting that the language is simple and the quality has improved. "In the second Gulf war they were very good," says Kamil Erdogdu, China correspondent for Turkey's state news agency. "They got many things first; I used them many times." AFP and the European Pressphoto Agency recently agreed to sell Xinhua images abroad. "I'm not convinced [censorship] makes a whole lot of difference" for video and pictures, says Jim Laurie, a former ABC and NBC correspondent who now consults for China Central Television (which is also expanding abroad). "Bottom line is so important," Laurie continues, that "if you see a source of video that is reasonably good, reasonably reliable, and reasonably inexpensive, you'll access it."

So far the more established wire services seem to be taking a philosophical approach. The AP declined to comment, and AFP didn't respond to a request for comment by press time. But Reuters sees Xinhua's expansion as a sign of "the viability of the global landscape," a view shared by many media analysts, who believe Xinhua's popularity in emerging markets will be fleeting, a stop-gap until private news outlets can afford the higher-quality wires. To help companies make the jump, all three agencies offer coverage on a more affordable, à la carte basis (just global sports news, for instance). But this view assumes that Xinhua will be seen as a propaganda outlet for years to come.

In recent months, Xinhua has worked to change that image, partnering with the United Nations Children's Fund to cover the well-being of children on six continents, and installing dozens of public flat-screen televisions around Europe to show its feed. And even if the agency fails to improve its image, naked bias is not a handicap the way it was for TASS, the Soviet Union's 100-bureau news agency during the Cold War. True, Xinhua's coverage of the United States is hardly fair and balanced. Earlier this year, when the Pentagon unveiled a report on China's military ambitions, it was brushed aside by Xinhua, which called it " 'unprofessional,' guilty of ambiguities and inconsistencies." But to many the Chinese perspective now seems like just another ideological choice on the dial, an option as valid as Al-Jazeera, Fox News, or MSNBC. An African or Asian newspaper editor might find the bias less annoying than the Pentagon does, says Minxin Pei, a senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

A bigger problem is the fact that Xinhua is often face-rakingly boring, as one would expect from an organization that believes "news coverage should help beef up the confidence of the market and unity of the nation." A recent piece about Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao revealed how he had "mixed up his rock types" during a talk with schoolchildren and then owned up to it. CHINA'S PREMIER WINS PRAISE AS ROCK OF RESPONSIBILITY Read the headline. For real information, even government officials are known to read Western outlets. The rest of the world may continue to do the same.

With Angela Wu and R. M. Schneiderman

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.