Assad's Bizarre Instagram Account: Propaganda With a Comments Section

Is propaganda really propaganda when any old web user can challenge its message?

"I belong to the Syrian people," Syrian president Bashar al-Assad told the French journalist George Malbrunot, of the newspaper Le Figaro, earlier this week. "I defend their interests and independence and will not succumb to external pressure."

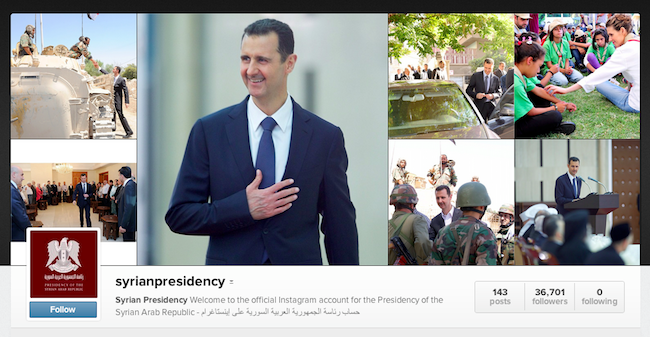

Yes. That's what he said. There are many, many caveats to that little assertion, obviously, but one of the most noteworthy is this: The message wasn't just sent from President Assad to George Malbrunot. It was also sent from President #Assad to George #Malbrunot. It was a message that originated in person, ostensibly, but that was delivered to the world (or at least to 36,664 members of that world) with the help of a Facebook-owned social network. It was political posturing in the form of an Instagram.

In that capacity, Assad's "Syria, c'est moi" messaging accompanied a picture of the president doing his thing, or claiming to -- one of dozens of such pictures that syrianpresidency, "the official Instagram account for the Presidency of the Syrian Arab Republic," has posted to its page since July.

The syrianpresidency feed is, to state the obvious, propaganda. It is also, to state the even more obvious, propaganda of the worst kind -- propaganda that insinuates and misleads and lies. It's not this that's going on in Syria right now, the feed insists; it's this. It's not neurotoxins and explosions and the violent deaths of civilians and children; it's science competitions and basketball games and, as my National Journal colleague Marin Cogan points out, Tiffany-blue fitness-tracking bracelets.

The account gives Syrians and non-Syrians alike a supposed little insight into the supposed little sitcom that is The Assads -- that quirky family-next-door, comprised of people who are wacky and relatable in equal measure. The Instagrams attempt to humanize Syria's first family, to place them in a familiar context -- which is also to say, if you've been following the news out of Syria, a totally unfamiliar context. A context that is unfamiliar because it is untrue. It's not, of course, that there's no joy to be found in Syria, despite all the conflict and chaos in the country; it's that syrianpresidency, with every implication of business-as-usual, commits a sin of informational omission.

Which is all to say that this particular Instagram feed does what most Instagram feeds tend to do: It offers a carefully crafted performance of daily banalities. With the difference here being that most Instagram feeds, and most of their mundanities, do not belong to dictators.

Here's another caveat, though -- one that might, as far as Assadian propaganda goes, be the caveat. An Instagram, as a bundled little unit of information, does not consist merely of pictures and post dates and captions; it consists, also, of follower feedback. Instagram's images come, by default, with comments. Which is perfectly natural -- most Internet Things come with comments fields these days -- but which is also, when a picture you've posted is propaganda, remarkable. Because, in the case of syrianpresidency, below the grotesque episodes of The Real Housewives of Damascus that play out on the feed, there are comments. Lots of them. Some of them insightful, some of them hateful, some of them both at the same time.

On an image of Asma al-Assad talking with Syria's top high school students:

What about all those children your husband slaughtered? They will never get a chance to attend high school.

On an archival image of a young Bashar al-Asad doing homework:

Future baby killer

On an image of Assad talking with a crowd of onlookers:

The syrian people love and support their benevolent protector Dr Bashar Hafez Assad ♡♡♡♡♡♥♥♥♥

This isn't, to be sure, discourse at its height. It is, for the most part, Internet commentary of an appropriately banal variety. But, then, the banality is the point. What it indicates is the fact that there's a community of people who felt entitled and perhaps even compelled to leave their marks on these images -- to add to them, to change them, to subtract a little spin and inject a little conversation.

Call it the mutualization of propaganda. Syria can say what it wants about itself and its activities; people, however, can now say things right back to it. They can scoff at the image being presented. They can express outrage at it. They can agree with it. The point is that they can react to it, publicly -- and their reaction can become part of the presentation of the image itself. Prominently and permanently displayed next to this image of Assad with arms outstretched is the Instagrammer hancoweiss's reply to it: "You have blood in your hands."

That is a significant shift. It changes what Syria is able to say about itself. It's the core logic of the Internet -- conversation, exchange, discourse that runs from top to bottom and vice versa -- brought to strategic messaging. It's what happens when propaganda, one of the most closed systems there is, meets the World Wide Web: a structure that is, by design, open. It's what happens when propaganda comes with a comments section.