Peter Kosminsky defends the BBC at the Baftas, 2016. Credit: BBC

The build up to, and aftermath of, the government’s white paper on the BBC reinforced a common pattern: a horror scenario was floated, protests were lodged, BBC figures showed their opposition to governmental demands for improvement but ultimately, as Nick Higham made clear, little 'will change fundamentally'. Des Freedman described this as ‘Apocalyptic rumours followed by a row-back and relief’, a ‘two-step strategy’ that the Conservative government has often used (especially with budget statements). The drama provoked demands to defend the BBC’s independence and neutrality, seemingly at any cost, and the BAFTA awards ceremony became a role-call of celebrity protest along these lines. When Peter Kosminsky, the director of Wolf Hall, collected the award for Best Drama Series, his speech echoed a number of well-worn assertions:

"Most people would agree that the BBC’s main job is to speak truth to power – to report to the British public without fear or favour … It is a public broadcaster – independent of government – not a state broadcaster, where the people who make editorial decisions are appointed by the government … All of this is under threat, right now … And you know what? It’s not their BBC, it’s your BBC. In many ways our broadcasting … is the envy of the world and we should stand up and fight for it. "

As we have described elsewhere, this conflation of ‘your’ and ‘our’ shows the BBC’s ability to create a public from within itself without any real reference to the people. Kosminsky’s warning is a familiar misunderstanding of what is or isn’t the state, and the BBC’s ability to create mediating institutions within it. The BBC certainly is a state broadcaster, but it is one whose power derives from its ability to distance itself carefully from the ‘core’ of state using intermediaries steeped in the jargon of neutrality: the soon-to-be-replaced BBC Trust for example.

Period drama and public memory

A couple of further issues are suggested by the BAFTA warning. Firstly, the cachet of historical dramas and their relationship with the heritage industry and, behind this, the BBC’s desire to converge archiving and public memory creation. Such is the BBC’s embeddedness in state machinery that documentaries and dramas are quietly charged with producing saleable versions of history as history. It is now common, for example, for BBC documentary histories to present their own footage as a memory of the time without any acknowledgment of this mediation. For example, Dominic Sandbrook’s series on the ’70s, illustrates the move from beer to wine with a scene from Whatever Happened to the Likely Lads?, as if the BBC’s televisual output is itself history. And this maps onto the creation of ‘a public’ supposed to correspond to the people. Secondly, the envy Kosminsky describes is the envy of how the entangledness of the BBC with economic and foreign policy and its tacit backing as a voice of Britain allows it an extraordinary niche from which it can leverage its own apparent neutrality and impartiality.

The BBC Two historical drama 'Wolf Hall'.

The BBC is in this sense a virtual monopoly broker of heritage. Heritage is not the same as history, which people have actually experienced, it is an economically-driven story of history in this case licensed by the wide state and having to draw some degree of participation by the people it encodes as the public – that is, it has to be seen to be loved. The heritage carrier is always in danger, and always having to be saved by a public who love it. This public has to lie at one remove from an apparent core of state conflated with the state itself, and perhaps, in this vein Kominsky’s comments can be taken as misleadingly identifying the state with just the buildings in Whitehall and Parliament. Particularly pronounced after the mid-twentieth century, the mediation of history as heritage both relies on ‘we, the public’, and is central to the adaptation of Britain’s economic role in the world.

The BBC itself, acting as producer, licenser, and audience all at once, frequently slides between description of content and description of heritage, as in ‘What the world thinks of British TV’, which reports that ‘foreign programme sales’ rose during and immediately after the double celebration of 2012, with the Golden Jubilee and London Olympics. London 2012, of course, was a set of object lessons in recuperating past images of public togetherness for private profit and the Olympic opening ceremony insisted on a welfare-state retro projection of ‘This is for Everyone’ in one of the most privatised environments in the world. In this sense, the BBC’s natural role in the heritage industry belongs to a much longer adaptation of colonial empire to subjective economy that had been taking place since the middle of the twentieth century.

The BBC and the neutral ‘us’

What is really unique in such pushes is the ability to mobilise popular participation as itself a brand – the source of the welfare-state retro increasingly visible after 2008 and collected in the Olympics opening ceremony, and also the authoritative ground of the licence fee which is both apparently voluntary and also legally taken as universal. The BBC Trust defines those liable to fund the Corporation through the licence fee as not only as TV owners, but also ‘any other person in the UK who watches, listens to or uses any BBC service, or may do so or wish to do in the future’. This extraordinary claim for all time is apt, since the BBC speaks for and on behalf of an organic British settlement that is not made by any people at any point. Rather, it seemingly just happens through a public ‘us’ that is without people and that no one has defined. It is ‘for everyone’ without anyone specifically opting in. In this mythology, neutrality is held to have given birth to a natural collective British ‘us’, and this comes through in Guardian comments’ reaction to the White Paper panic, claiming that the BBC was being victimised because the government don’t like ‘collectivism’.

The London Olympics opening ceremony, 2012. Credit: Morry Gash / PA Images

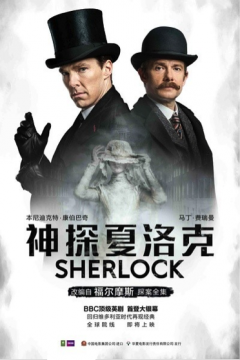

More widely the BBC brand in the heritage industry relies on the sacral neutrality that is rehearsed during every scare like the White Paper. Neutrality, moreover, is itself a central theme driving overseas sales, and relying on the BBC’s constitutional embeddedness. Sherlock’s popularity in China is a prime example. An East Asian market for British (really London) Victoriana has been established for a while, and draws on the rise of an ideology of neutrality in the Victorian empire itself, a literary canon claiming global civilizing powers, the paraphernalia of rational gentlemanliness in Holmes and now his conduit Benedict Cumberbatch, and behind these the calm authority of the financial capital. In such apparently neutral realms exceptional quality naturally floats to the top, and this neutralist exceptionalism is increasingly celebrated as content.

Founding role of the state broadcaster

Chinese publicity for BBC drama 'Sherlock'. The BBC was created not through some spontaneous popular demonstration but right at the heart of the state, by laissez-faire empire loyalists, and as the primary vehicle for these neutral claims to British exceptionalism. It follows a long era during which the core need for neutrality was taken from colonial occupation to be ‘cultured’ via a number of interlocking constitutions, including civil service testing, literary education, the expectation of gentlemanliness and all the various civilities of the Anglosphere. The BBC was to act as a coda for claims to neutrality and exceptionalism, and transmit them across the commonwealth.

Comparable to and drawing from the General Post Office’s previous role in public communications, the BBC was an archetype of the modern public corporation, and after its 1927 Royal Charter commissions have regularly concluded that, as the 1951 Beveridge Report (on Broadcasting) put it, the Corporation ‘carries with it such great propaganda power that it cannot be trusted to any person or bodies other than a public corporation’. John Reith stressed the importance of BBC governance establishing a ‘unity of control’. As early as 1925, the Crawford Report was arguing that ‘only the state could license the BBC to be “a public corporation acting as a trustee for the national interest”’. But James Curran and Jean Seaton date the rise of the BBC’s performance of neutrality, or what they call the point at which ‘the BBC invented modern British propaganda’, more specifically to the 1926 General Strike, a time when, as Michael Tracey describes, there was ‘detailed co-operation between the government and the BBC to get the miners back to work’.

Although the BBC did occasionally censor in the 1930s, it increasingly relied on a performance of transparency, which would gradually itself be thematised and fed it into its claims to political balance, that is, a form of competition enshrined in the BBC guidelines as ‘a wide range of significant views and perspectives’. The great emotional claim of neutrality, though, comes after the massive consolidation of cultural agencies in the wartime emergency of 1939-42 (the Ministry of Information, the Council for the Encouragement of Music and Arts, the British Council, the Board of Education), when neutrality could be explicitly fitted to the instrumental demand of public morale. During this period the BBC was able to join the exceptionalist story of global neutrality to the love of domestic audiences, and as Sian Nichols puts it, ‘empire was again a persistent theme in British domestic as well as overseas broadcasting’.

The World Service, established as the Empire Service in 1932, and funded by government grant-in-aid, remains a pivotal policy conduit. Reacting to a 2011 scare over cuts to the World Service, in his Institute of Commonwealth Studies lecture Philip Murray described how ‘[i]f you’re going to have a serious foreign policy you should concentrate on what you’re good at, and in Britain’s case that’s the BBC’. Policy increasingly converged with the BBC’s reputation as solid, reliable, neutral, and public, and the BBC increasingly understood the demand to mobilise British heritage to align its global economic role with domestic public opinion. William Beveridge cited the need for the unification of public opinion to recommend the continuation of the BBC monopoly.

Citizenship as brand loyalty

This grip on public opinion – in our own times increasingly read, of course, through welfare state retro – is part of what is at risk from what is described as ‘private sector’ contamination, and part of the reason no British government really wants to risk the BBC brand. Even the most ‘privatising’ governments appreciate this – Thatcher administrations, for example, as seen in the 1992 document ‘The Future of the BBC’. If one thing is clear from the current White Paper controversy, it is the ongoing need for ‘distinctiveness’, an encoded demand for a tightening of the BBC’s British branding credentials.

PM David Cameron in China, 2013. Credit: Stefan Rousseau / PA Images

Plus, the BBC’s branding tends towards a continuum with state policy, not some kind of popular check on it. And this already exerts a power over the whole media: the power of the BBC’s virtual monopoly on heritage, archive, and the visual and legal signs of the public, forces other providers to echo its formats and bask in the shadow of its cultural capital, its heritage-ism, its definition of balance, its institutional feedbacks, its neutrality claims (Downton Abbey most obviously, often taken as a BBC production but in fact an ITV one). The story of privatising dangers averted at the last moment segues seamlessly into the need to protect the BBC as a national brand with global reach, and this homely defence must be made domestically to have the authenticity to work overseas. This has been particularly true of a heritage-driven economy that has been increasingly comfortable in portraying its claimed nation as a brand.

The BBC then is central to the branding mobilisation of public neutrality. The degree to which this branding of neutrality has come naturally to Britain with the long ‘culturing’ of physical empire can be readily tracked. It is seen in the way London itself has become a degree zero of nation-branding. In fact, as Melissa Aronczyk shows, virtually all the active nation-branding consultants to be found anywhere in the world are based in London. Nation-branding in Aronczyk’s description looks much like the BBC’s mission – it is an overseas message that must also be performed at home: people ‘“live the brand”… perform[ing] attitudes and behaviours that are compatible with the brand strategy… “immersing” themselves in the brand identity’. This is a vision of the national that is both patriotic and instrumental, that is rigorously politically neutral because it is ultimately not political at all, but ‘rooted in the unifying spirit of benign commercial “interests” rather than in the potential divisions of political “passions”’. It is a prestige continuum for which cultural claims to neutrality and the thematising of neutrality can simultaneously be celebrated for their economic core, in which the gritty ‘realities’ of the City of London are also familiar and domestic, as in the opening titles of the UK Apprentice series. With the entanglement of citizenship and brand loyalty this kind of milieu demands, there are obvious rewards for outraged defences of the not-a-state state broadcaster.

Michael Gardiner and Claire Westall are authors of 'The Public on the Public: The British Public as Trust, Reflexivity and Political Foreclosure ' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014)

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.