The discovery of fragments of ancient cuneiform tablets – hidden in a British Museum storeroom since 1881 – has sparked a diplomatic row between the UK and Iran. In dispute is a proposed loan of the Cyrus cylinder, one of the most important objects in the museum's collection, and regarded by some historians as the world's first human rights charter.

The Iranian government has threatened to "sever all cultural relations" with Britain unless the artefact is sent to Tehran immediately. Museum director Neil MacGregor has been accused by an Iranian vice-president of "wasting time" and "making excuses" not to make the loan of the 2,500-year-old clay object, as was agreed last year.

The museum says that two newly discovered clay fragments hold the key to an important new understanding of the cylinder and need to be studied in London for at least six months.

The pieces of clay, inscribed in the world's oldest written language, look like "nothing more than dog biscuits", says MacGregor. Since being discovered at the end of last year, they have revealed verbatim copies of the proclamation made by Persian king Cyrus the Great, as recorded on the cylinder. The artefact itself was broken when it was excavated from the remains of Babylon in 1879. Curators say the new fragments are the missing pieces of an ancient jigsaw puzzle.

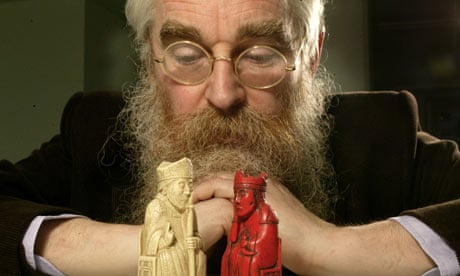

Irving Finkel, curator in the museum's ancient near east department, said he "nearly had a coronary" when he realised what he had in his hands. "We always thought the Cyrus cylinder was unique," he said. "No one had even imagined that copies of the text might have been made, let alone that bits of it have been here all along."

Finkel must now trawl through 130,000 objects, housed in hundreds of floor-to ceiling shelving units. His task is to locate other fragments inscribed with Cyrus's words. The aim is to complete the missing sections of one of history's most important political documents.

The Iranians have been planning to host a major exhibition of the Cyrus cylinder ever since MacGregor signed a loan agreement in Tehran in January 2009. I was in Iran with the museum director, reporting for BBC Radio 4 on his mission of cultural diplomacy.

Six months before pro-democracy protests were met with violence in the wake of the presidential election, tea and sweet pastries were offered to the British guests at the Iranian cultural heritage ministry. MacGregor was there to meet Hamid Baqaei, a vice-president and close ally of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Their friendly discussion was a significant diplomatic breakthrough at a time when tensions between Britain and Iran had been strained to breaking point after the expulsion of British Council representatives from Tehran. The recent launch of the BBC Persian television service had also been interpreted as a provocation by London.

With even the British ambassador in Tehran struggling to maintain a dialogue, MacGregor was the sole conduit of bilateral exchange in January 2009. The sight of a miniature union flag standing alongside the Iranian flag on the table between the British Museum boss and his Iranian counterparts boded well for an amicable meeting. In previous weeks, the only British flags seen in public in Tehran were those being burned on the streets outside the embassy.

MacGregor's objective was to secure the loan of treasures from Iranian palaces, mosques and museums for the museum's exhibition on the life and times of 16th-century ruler Shah Abbas. Discussions over the loan of treasures relating to one great Persian leader prompted the suggestion that another – Cyrus – could play a part in a reciprocal deal.

MacGregor may have been put on the spot by Baqaei, but he agreed to a three-month loan by the end of 2009. A year later, Baqaei's tone towards MacGregor is not so friendly. Quoted by the Fars news agency in Iran, he accused the museum of "acting politically". Further "British procrastination" would result in a "serious response" from Iran.

The Cyrus cylinder remains a compelling political tract more than two and half millennia after its creation. Accepting her Nobel peace prize in 2003, the Iranian human rights lawyer Shirin Ebadi cited Cyrus as a leader who "guaranteed freedoms for all". She hailed his charter as "one of the most important documents that should be studied in the history of human rights".

In 2006, the then foreign secretary, Jack Straw contrasted the freeing of Jewish slaves by Cyrus with Ahmadinejad's "sickening calls for Israel to be wiped from the face of the map".

David Miliband, the current foreign secretary, has yet to reflect on the contemporary resonance of Cyrus in a country in which human rights have been violently curtailed of late. But a spokeswoman for the Foreign Office said: "It is a shame that the British Museum has felt compelled to make this decision." She added that "we share the British Museum's concern that this would not be a good time for the cylinder to come to Iran" owing to the "unsettled" situation in the country.

Last week MacGregor presided over a launch, at the British Museum, of the History of the World in 100 Objects, his collaborative project with the BBC. The director is presenting a 100-part series on Radio 4, in which the story of mankind is told through individual artefacts. The Cyrus cylinder was considered for inclusion, but did not make the final hundred.

Some guests at the launch, when told how the discovery of the new fragments had delayed the loan of the Cyrus cylinder, were suspicious. "Fancy that, what a stroke of luck," said one. "That gets Neil out of a jam for now."

The director himself says he is determined that the cylinder will eventually be lent to Tehran, along with the newly discovered fragments, to tell a better story about Cyrus. He says he can understand the frustration and anger in Tehran, but it will be worth their wait.

They may well be getting more than they bargained for. To the Ahmadinejad regime, the cylinder is an iconic object, one that fuels collective pride in national heritage. But to those who are fighting for freedom of expression in Iran in the face of violence, the return of Cyrus could offer a potent new rallying point.