hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

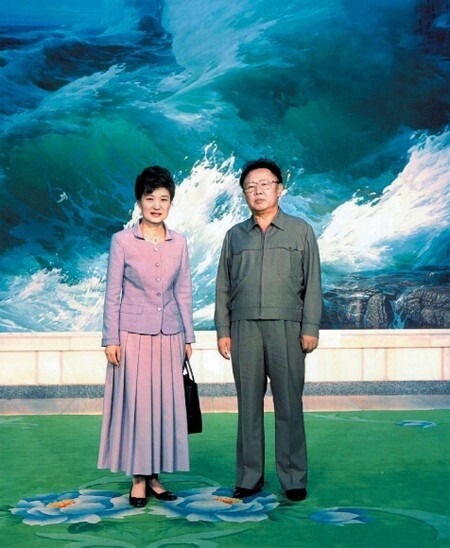

Park Geun-hye’s North Korea policy

By Kang Tae-ho, senior staff writer

From her statements and pledges during the election, president-elect Park Geun-hye’s plan for North Korea policy appears less antagonistic than the Lee Myung-bak administration’s approach, but not as conciliatory as that of the Roh Moo-hyun administration. As a presidential candidate, she tried to contrast her own platform with Lee’s failed policies without signing on for the engagement approach favored by Roh, and by Kim Dae-jung before him.

During the election campaign, Park said there needed to be “an evolution” in North Korea policy.

“I plan to break with this black-or-white, appeasement-or-antagonism approach and advance a more balanced North Korea policy,” she declared at the time. This would suggest her approach will fall somewhere between Roh’s and Lee’s. But it’s still unclear what Park meant by “evolution” or “balance.”

The same is true for her foreign policy approach in general. She has said she wants to deepen the comprehensive strategic alliance with the United States and take the strategic cooperative partnership with China to the next level. However, Park has not yet explained how she plans to proceed if Washington and Beijing’s interests clash, or if they conflict with her own North Korea policies. As former Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade Song Min-soon so aptly put it, she has offered nothing more than “hopeful generalities, missing even a way to finish the baby steps of nuclear disarmament that were stopped in their tracks four years ago.”

Back on Nov. 5, Park announced her vision for foreign relations, national security, and unification policy, an idea she called “diplomacy of trust and a new Korean Peninsula.” The measures she described emphasized an incremental approach over radical changes in inter-Korean relations.

First, she would push to have inter-Korean exchange and cooperation offices set up in Seoul and Pyongyang to promote social and cultural interchange in such areas as public health, religion, and scholarship. The idea is to build trust, with plans for ushering in an internationally supported “Vision Korea” project once North Korea makes positive steps toward denuclearization. This project would involve setting up a pan-Korean economic community, which was the second phase in the reunification plan enacted under the Kim Young-sam administration, South Korea’s second democratically elected government after Roh Tae-woo’s presidency in 1988 to 1993. Specific ideas included internationalization of the Kaesong Industrial Complex, joint exploration of underground resources, and a South Korean presence in North Korea special economic zones such as Rajin/Sonbong.

Park Jong-chul, a senior research fellow at the Korea Institute for National Unification, described this as “an attempt to preserve continuity with the Lee Myung-bak administration’s North Korea policies, while distinguishing itself with an emphasis on policy growth and gradual improvements in our relations with Pyongyang.”

But while it avoids the rosy predictions of Lee’s “Vision 3000” plan, as well as its demand that Pyongyang end its nuclear program before any other steps are taken, it also continues to tie the state of inter-Korean relations to North Korea’s nuclear program. Park’s policy emphasizes a powerful deterrent to discourage North Korea from pursuing its nuclear program and ensures it pays a steep price for any provocations. This is, in the broader scheme of things, nearly identical to Lee’s approach. Indeed, in an open letter in question format issued on Dec. 1 by the Committee for the Peaceful Reunification of Korea, North Korea’s agency for South Korea policy, Park’s calls for Pyongyang to end its nuclear program before any further steps from Seoul were described as essentially the same idea as Lee’s Vision 3000 plan.

For the moment, Pyongyang is taking a wait-and-see approach. The Choson Sinbo, published by Japan’s pro-North Korea General Association of Korean Residents, brought the open letter up again in a Dec. 21 article titled “The Question: A Second Lee Myung-bak?” which appeared to ask Park to clarify her position now that she is president-elect.

In a Jan. 2 article, the Choson Sinbo wrote, “Kim Jong-un’s New Year warning message is intended to urge Park to make a bold policy shift, as she has insisted on differentiation between her and Lee Myung-bak”.

Some positive signs were evident in statements by Ewha Womans University professor Choi Dae-seok, who voiced Park’s position on North Korea policy when he was part of her election camp and is now a member of Park’s transition team. Speaking at a debate for the 50th Kyungnam University Unification Strategy Forum in August of last year, Choi acknowledged some differences in opinion in the “progressive” and “conservative” positions on three key issues in North Korea policy, but added that most of them were narrowing. The three issues he identified were the question of whether to adhere to the terms of the June 15 and October 4 Joint Declarations between Seoul and Pyongyang, whether to prioritize inter-Korean relations or North Korea’s nuclear program, and how to proceed with the so-called “May 24 measures” taken by the South Korean government after the 2010 sinking of the ROKS Cheonan, as well as whether North Korea should apologize for the sinking.

According to Choi, the issue of the declarations was something that could be addressed in discussions with North Korea, and there was no real argument about the need to continue abiding by their terms. He also said there was no major disagreement on the nuclear issue, which both sides agreed should be resolved from a long-term perspective - tied in some ways to inter-Korean relations, but with some degree of flexibility. He also argued that Seoul needed to get away from schematic definitions of what needs to come “first” and “next” in terms of relations with North Korea and the nuclear program.

However, he drew the line at questioning the Cheonan investigation findings and demanding a reinvestigation.

“Obviously, there needs to be an apology from North Korea first,” he said. “To reject the Cheonan investigation findings and demand another investigation goes beyond distrust of the government, and it does not accord with the public’s sentiments.”

Park herself addressed the Cheonan issue while talking with journalists in August. “It was a terrible incident where many young soldiers lost their lives,” she said. “While it would be irresponsible for the government to suggest pretending it is not an issue, it’s also not good for things to continue on in this way.”

It would be premature to make predictions about how inter-Korean relations will be under the next administration based solely on the platform outlined during the campaign. The pledges represented hopeful ideas designed to win votes, not actual policies. And the course of inter-Korean relations and actual policies is unquestionably going to be determined in the context of the political interests of other countries with a stake in the peninsula, notably the US and China.

Park has pointed to the need for strong security measures, but she has also stressed the importance of dialogue. She has said that she will not demand any conditions for dialogue with Pyongyang, and that she is willing to meet with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un if it would help improve inter-Korean relations. The question that needs to be answered now is whether she only plans to engage in dialogue once Pyongyang has made gestures of trust, or whether she hopes to build trust through dialogue. The crux of this is the kind of message she sends to North Korea.

In “A Message of Thanks to the People,” her first press conference after winning the election, she said on Dec. 20 that North Korea’s long-range missile launched “provided a symbolic picture of how serious the security situation we face is.” However, she did not elaborate. Her more reticent approach provided a clear contrast with the approach taken on the same day five years ago by then-president-elect Lee Myung-bak, who hinted at the hard line on Pyongyang to come when he told South Korean and foreign reporters his would be “a different administration from the ones that tried to curry favor with North Korea.”

Early on, Lee attempted to distinguish his own policies from the “successes” of the preceding Roh Moo-hyun administration. But his approach ended up a failure, breeding conflict and frictions with Pyongyang with its demands for unilateral capitulation. The Lee administration found itself a passive participant in inter-Korean relations, depending on a resumption of the six-party talks on the nuclear issue to reopen dialogue. If Park and her presidential transition committee agree on the need to open up some kind of dialogue with Pyongyang - while continuing to maintain an active deterrent in the interests of national security - then they will need to distinguish their future policies from Lee’s failed ones. Specifically, they will have to use them as the starting point in a trust-building process, forcing North Korea to decide whether or not it is willing to talk.

Park’s response to North Korea’s recent successful rocket launch will be key. While it is unclear just what kind of sanctions are on the way, it has already been demonstrated that sanctions of any kind are ineffective without Beijing on board.

Indeed, a hard-line approach could give North Korea a pretext for a third nuclear test. A spokesperson for the country’s foreign ministry already warned that by showing a “hostile overreaction to our [attempted] satellite launch in April,” the United States “forced us to completely reconsider the nuclear issue.” Any trust-building process to come faces a serious obstacle from the outset.

This means some way around it will have to be found. One helpful approach may be the strategic dialogue with Washington and Beijing that Park mentioned in her platform. This means the new administration would have to position China as an active mediator, with the condition that North Korea abstain from any additional nuclear tests. Park could get things moving again with preliminary steps to resume the six-party talks by encouraging a return to and expansion on the agreement made between Pyongyang and Washington this past Feb. 29, including a halt to rocket launches. This could very well open up the possibility for a turnaround that would lead into a trust-building process on the peninsula.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 2AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 3Noting shared ‘values,’ Korea hints at passport-free travel with Japan

- 4Two factors that’ll decide if Korea’s economy keeps on its upward trend

- 5Why Kim Jong-un is scrapping the term ‘Day of the Sun’ and toning down fanfare for predecessors

- 6South Korea officially an aged society just 17 years after becoming aging society

- 7Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 8Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 91 in 5 unwed Korean women want child-free life, study shows

- 10[Reportage] On US campuses, student risk arrest as they call for divestment from Israel