When China and France went to war: 130 years since forgotten conflict

A soft-power approach has seen a strong bond develop between Hong Kong and the French, unlike 130 years ago, when France went to war with China. Stuart Heaver looks back at a forgotten conflict.

Few expatriate communities make so vibrant and welcome a cultural contribution to Hong Kong as the French. So it'll probably come as no surprise to learn that, this weekend, hardly anyone will be marking the 130th anniversary of a little-known war between France and China that created such antipathy towards the European nation that there was a boycott and riots on the streets of Hong Kong.

"Every man has two countries; his own and France." The epithet is attributed to American founding father and third president Thomas Jefferson and it applies particularly to Hong Kong, where the number of French expatriates has been expanding rapidly and their culture and influence seems ubiquitous.

Over recent months, the city that magazine calls the "Gallic capital of Asia" has witnessed Le French May arts festival; the visit of French warship Prairial; the "Palaces on the Seas" exhibition at the Maritime Museum, celebrating the golden age of French passenger liners; and Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying being guest of honour at the French national day reception. French football giants Paris Saint-Germain were cheered on as they thrashed Hong Kong's Kitchee and locals quip that it's now easier to find a fresh baguette in Sheung Wan than it is a bowl of noodles.

Live the history of Hong Kong, how it grew from colonial opium trading outpost to global finance mecca

This year also marks the 50th anniversary of the opening of diplomatic relations between France and Communist China. Urged on by President Charles de Gaulle, in 1964, the French became the first Western nation to recognise the new government in Beijing, much to the disgust of the Americans. A long established diplomatic bond of trust exists between the two nations, albeit a bond that has been stretched on one or two occasions. Who would have thought, even 20 years ago, that the French and Chinese would be cooperating to build nuclear power plants in Britain?

One hundred and thirty years ago, the relationship was far more frosty. On August 23, 1884, France and China went to war with each other. Few seem to have heard of the nine-month conflict that made the French personae non gratae on the streets of Hong Kong.

It was by no means an obscure or minor historical event, either. It has been estimated that the war on land and at sea caused more than 15,000 casualties on the French, Chinese and Vietnamese sides; it stopped China's self-strengthening movement in its tracks; it brought down the expansionist French government of Jules Ferry; it defined future French colonial policy in Asia; and it almost brought France and Britain into conflict with one another. Strangely, war was never formally declared by either side and there is no consensus as to who actually won it.

"I have to admit I have never heard of it," says Agathe Heidelberg, the Parisian director of Marc & Chantal, a creative agency in Sheung Wan.

"Over the last 10 years, what is happening in the French community is just crazy," says Heidelberg, who arrived with her husband, Jean, a decade ago and now lives with their three young children in Stanley.

Hong Kong's French population has trebled since 1998; the French consulate estimates that more than 17,000 now live in the city.

"Asia is the attraction as a business venue - especially China - but Hong Kong is much easier than the mainland and more exciting, too," says Heidelberg, explaining the appeal. "This is just a great place for those who want to start their own business.

"Every week I have a [French] friend e-mailing me saying they would like to visit to look at the market and maybe live here," she says.

And Heidelberg believes the French might have an edge over their European rivals.

"Maybe with luxury or high-end clients, we have an advantage in that our customers perceive that the French have an intrinsic understanding of luxury, that there is a French touch, that we have ," she says.

Funnily enough, French business advantages and access to China were also what caused the Sino-French war.

"Influential French businessmen hoped to establish an extremely profitable overland route with China, bypassing the treaty ports of the Chinese coastal provinces," says David Wilmshurst, author of a new book on the war, titled .

Wilmshurst says the conflict was a result of France's colonial ambitions in Tonkin (northern Vietnam), which the French government thought could provide a direct trading route via the Red River to the southwestern provinces of China.

"The French regarded the British as highly ambitious and felt they needed to secure Tonkin before the Brits grabbed it," says Wilmshurst.

Unfortunately for the French, China considered Vietnam a tribute state and military conflict had been raging on and off in Tonkin between the French and a pack of fearsome bandits sponsored by the Chinese known as the Black Flag Army since the previous year. It was actually the conclusion of these hostilities that triggered war, when Chinese troops failed to honour the peace accord and massacred an advancing French column.

The infamous Bac Le ambush, in June 1884, caused outrage in Paris and a public appetite for revenge.

The wily and adept Admiral Amedee Courbet was tasked with bringing the recalcitrant Chinese into line and his naval squadron amassed in the busy treaty port of Fuzhou.

As the Chinese reinforced their defences and diplomatic efforts stumbled, every step of the tense confrontation was avidly read in the Hong Kong press.

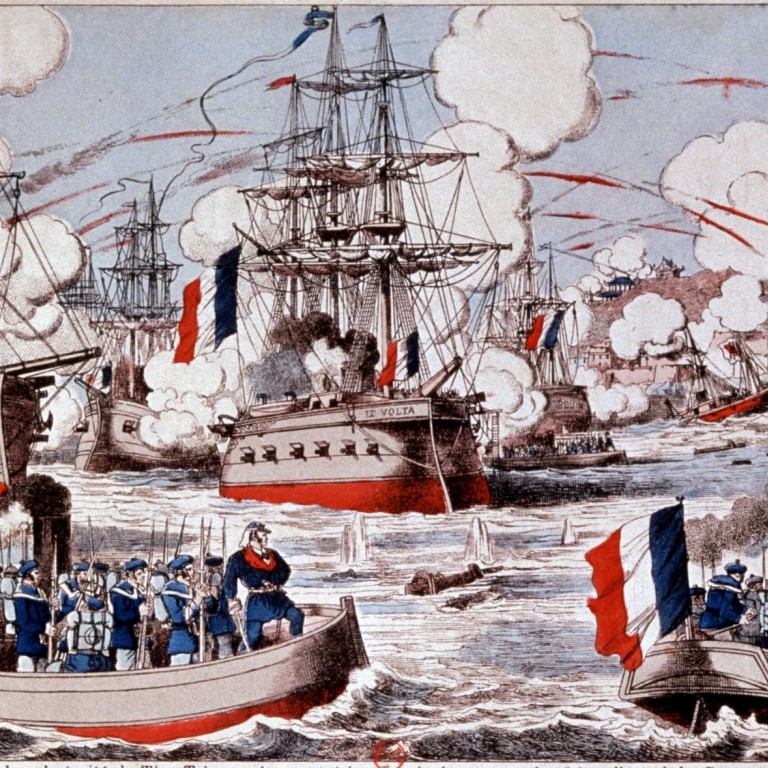

At 2pm on August 23, 1884, Courbet opened fire on the Chinese southern fleet anchored in the Min River, a few miles downstream from the city of Fuzhou. On the eve of the battle, Courbet made a point of warning every neutral ship in the port of the carnage that was about to ensue.

"Late at night when the young midshipman delivered the message to British Admiral [William] Dowell anchored nearby, Dowell poured the exhausted young French officer a whisky and wished him ' '," says Wilmshurst.

It is estimated that the Battle of the Pagoda Anchorage lasted less than 10 minutes and the commissioner of customs in Fuzhou reported that, "It cannot be called a battle, it was a butchery."

The crews of naval and merchant ships of many other nations anchored in the roadstead were spectators as Courbet systematically destroyed the Chinese ships and the modern naval shipyard and arsenal on the Min River, which had been constructed under the supervision of the French navy only a few years earlier.

"As victorious Admiral Courbet sailed through the ranks of the anchored ships, there was spontaneous applause and cheering from the neutral vessels," says Wilmshurst.

Support was far from universal, though, and as Courbet carefully exited the Min River, destroying the Chinese defences en route, and proceeded with the occupation and blockade of northern Taiwan, sympathy for the French started to evaporate rapidly as commercial shipping was disrupted and neutral ships were turned back from the Taiwanese coast by French warships.

The irritation in European business circles, though, was nothing compared to the animosity felt on the streets of Hong Kong. When La Galissonniere, the flagship of Courbet's second in command, Admiral Sebastien Lespes, and small torpedo boat No 46 entered Victoria Harbour in early September 1884 for much-needed repairs following the battle off Fuzhou, local dockworkers, stirred up by the authorities in Canton (Guangzhou), refused to help.

"The Chinese boating people in the colony seem determined to earn the title of patriots during the present position of affairs between France and China and decline to earn an honest penny if the job offered be in any way connected with the French," reported the , on September 23, 1884.

The Galissonniere eventually found less-principled Hong Kong workers, but there were genuine fears for the safety of the ship's company.

"The British had to allocate Admiral Lespes a special guard of armed Sikh policemen," says Wilmshurst.

When the anti-French strikers were prosecuted by the indignant colonial authorities, who were intolerant of any interruption to usual business practice, it provoked violent riots in the streets. Again, the authorities in Canton helped fan the flames.

Under the headline "Serious Riots in Hong Kong", the on October 3 reported that "the riot of this morning was the most serious one that has ever occurred in Hong Kong".

As the East Kent regiment was deployed with bayonets fixed to quell the riots and, for the first time, members of the Chinese merchant elite were engaged to try and pacify the mob, the British, too, turned against their bellicose European neighbours. Disruption to shipping was costing them money, the rapid growth of the French Far East squadron was making the Royal Navy uneasy and the French were able to use Hong Kong freely as a neutral port because they refused to formally declare war on China. Rumours of French cruisers boarding British merchant ships were widely considered a step too far.

"There is a report in circulation that Admiral Dowell has been in telegraphic communication with the authorities at home in regard to the searching of British vessels by French cruisers," reported the , on October 6, as the riots continued.

On October 10, just after the worst of the rioting, a young French naval hydrographer, Rollet de l'Isle, revisited Hong Kong and recorded in his journal the distinctly chilly welcome he received.

"A sullen hostility still reigns as evidenced by the fact that we were not met by the crowds of sampans that usually surround our ships when we put into harbour," he wrote.

The war raged on until April 1885 and a peace accord was signed on June 9. The accord ceded Tonkin to France (eventually to become part of French Indo-China) while the Europeans agreed to withdraw from Keelung, in northern Taiwan, and from the Penghu Islands (now a county of Taiwan, also known as the Pescadores Islands), which Courbet had successfully captured on March 31, 1885.

Courbet wanted to retain the Penghus and see the islands be developed into the French version of Hong Kong but, following a humiliating defeat in the land war in Tonkin during the Lang Son Campaign, Ferry's government had fallen. No one in Parisian political circles had any appetite for further conflict and Courbet never made it back to France. He died of dysentery in the Penghus the same year and a memorial to the admiral can still be seen at the side of a busy road junction in Magong, the islands' only city.

If this easily forgotten war that made France so unpopular was driven by commercial motivations and the desire for a trading gateway to China, might the wonderful French culture that we enjoy around this city today be a coordinated assault to support modern-day commercial interests?

"I would not choose the term 'assault'," says France's consul general to Hong Kong, Arnaud Barthelemy, a suave and erudite man who describes himself as a career diplomat with a business background. ("I am not here as a Chinese expert, I am here as a business expert".)

Barthelemy, speaking in his office on the 26th floor of Admiralty Centre, estimates that one-third of his time is spent on economic and business matters and confirms that an increasing number of his countrymen are coming to Hong Kong because of the opportunities that exist here for French business, big and small.

"Clearly there is a strong political willingness on both sides to develop our relations with China and Hong Kong in all fields because this is absolutely key. The relationship is multi-faceted," he admits. "We have a tradition to encourage as much cultural dialogue as possible and this is part of our diplomacy.

"[Cultural dialogue] is good for business, too, because it helps to establish brand France," says Barthelemy.

What would Courbet, who preferred a naval broadside, have made of cultural exchange and brand development?

Barthelemy seems a little reluctant to chat about the war of 1884 or discuss how well-known he thinks the conflict might be in Hong Kong's French circles.

"Honestly, not much. Clearly the focus is on the future. And our past in Hong Kong was not just about business," he says, pointing to an impressive book titled , which was produced by the consulate and partially designed by Heidelberg's company. Here, among the anecdotes relating to worthy and notable French contributions to Hong Kong, you can find a brief account of the French boycott and a picture of the Galissonniere.

"It was about religious people, scientists, explorers, of course, some merchants, but these are not the majority," Barthelemy says.

The statistics indicate that, in economic terms, the entente cordiale fostered by the current charm offensive is working even more effectively than Courbet's naval strategy did 130 years ago. According to consulate figures, more than 750 French companies are operating in Hong Kong, 66 of them with regional headquarters here. They employ about 33,000 people and generate a turnover of HK$110 billion. French exports to Hong Kong have more than doubled over the last five years and in business as well as cultural terms, the French seem to be everywhere.

"Few people know that all HSBC transactions are secured with French technology and that Hong Kong ID cards use a French operating system," says Barthelemy.

then, has been replaced with the charm offensive, and it is making more friends for brand France than gunboat diplomacy ever did - and is proving better for business. But the bloody Sino-French war had an indirect benefit for China that few recognised at the time.

Many scholars now identify the patriotism and civil disobedience that were witnessed on the streets of Hong Kong and inspired by the French aggression in Fuzhou as the first rumblings of Chinese nationalism in the colony. The development of this public sentiment would help create the modern Chinese republic in 1912.

So, even in those distant days of war and discord, France was managing to make an important contribution (albeit unwittingly) to the development of Hong Kong and China.

…