Report / Vatican City

Vatican foreign policy: Keep the faith

Like many sovereign states, the Holy See pursues an active foreign policy, wielding enormous influence on international decision-making. We visit the Vatican’s foreign ministry, where world peace is always on the agenda.

With a broad smile and swish of his cassock the pope’s private secretary, archbishop Georg Gänswein, ushers us into the inner sanctum of the Apostolic Palace in Vatican City. We have already run the gauntlet of Swiss Guards attending the vast Portone di Bronzo doors, processed down loggias painted by Raphael, scurried along narrow passages, loitered in grand halls and been greeted by Vatican secretaries in crisp white tie. Now a buzzer sounds: our cue to move through a damask-lined door to watch Pope Francis bless a tray of official gifts for a delegation of guests.

This is diplomacy papal style; a combination of ritual, prayer and frank discussions on world affairs. Today the rosaries and olive wood are for an assembled group from Antigua and Barbuda who present a bright-yellow oil painting before being whisked away for talks. Indeed, this is just one of many diplomatic engagements on a tight papal agenda: in the past few days Francis has discussed the Minsk accords with Ukraine’s Petro Poroshenko, convened with the Jesuit Refugee Service and held talks with Hatem Seif El Nasr, Egypt’s ambassador to the Holy See. He is about to embark on a tour of central Africa.

Since the Argentine cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio was elected to become the 266th pontiff in 2013 he has pursued a hands-on approach to international relations. He played a direct role in brokering a historic rapprochement between Cuba and the US; he has made bold public reference to the Armenian Genocide and has spoken out on everything from the Italian Mafia to globalisation and its profound inequalities. In simple white robes and pointedly small cars, the leader of 1.2 billion Roman Catholics has been crafting a powerful soft-power profile and a sharp foreign-policy focus.

All this is supported by a papal diplomatic service that’s very often eclipsed by the headline-grabbing movements of the supreme pontiff. On the top floor of the Apostolic Palace is the Office of the Secretariat of State and its “Section for Relations with States”: the Vatican’s equivalent of a foreign ministry. Desk officers and foreign-policy experts (many are priests in black blazers and monsignors in flowing cassocks) stroll past huge 16th-century maps of the world to get to their offices. It’s clear from these gilded cartographic frescoes (where sea monsters splash near Africa) that the Holy See has had a keen eye on foreign lands for some years. Its first envoys were established in Venice and France in 1500 and the first ambassador to the Holy See was sent out by England’s Edward IV in 1479.

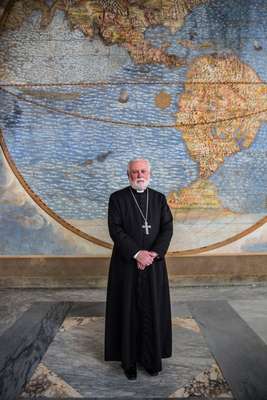

Today the Holy See has full diplomatic relations with 180 states and multilateral bodies, and has 100 resident ambassadors (Apostolic nuncios) stationed everywhere from Bogotá to Islamabad. Like conventional diplomats, lots of their work involves the gathering of information. “Both here and in our nunciatures – which correspond to our embassies – we try to understand what’s going on in world politics,” says archbishop Paul Gallagher, the Liverpool-born secretary for relations with states (foreign minister, in other words) who meets us in a gold room that adjoins his office. “We also try to interpret what its significance is for the Church and the Holy Father so that he can understand what’s at stake in world affairs, [so] whatever he’s going to say and do can be as well informed as possible.”

The pope’s nuncios are trained in the 300-year-old diplomatic academy of the Holy See behind Rome’s Pantheon (a place referred to simply as L’Accademia), before being dispatched abroad. Most are promoted to bishop before they leave. Though ambassadorial billets range from a brownstone in New York to a boxy modern compound in Brasilia and a small 19th-century cottage-like residence in Pretoria, many work in less hospitable climes. The Holy See still has a nuncio in Damascus and a Vatican embassy in the Sha’ra Saadoun district of Baghdad; its nuncio stuck it out through the shock and awe of 2003 and subsequent instability.

“In difficult and dangerous places I am always immensely proud that our nuncios nearly always want to persevere,” says Gallagher, who himself served in civil-war-torn Burundi after his predecessor archbishop Michael Courtney, who had been involved in brokering peace accords with rebel factions, was assassinated in 2003. Nuncios are also subject to diplomatic immunity in post, sometimes controversially. In 2014 a report by the UN Committee against Torture criticised Gallagher (then papal envoy to Australia) for invoking this status when refusing to provide documents that could assist prosecutors in an inquiry into sex abuse.

“We don’t oblige anyone to stay but one of the things I always say is that we’re in the thing for the long haul,” says Galagher. “We have a tradition of dedication. That tradition of commitment to communities and people is reflected in our diplomatic work. I know [our nuncios] feel not just a diplomatic and political commitment but also a pastoral one.”

Though the nuncios are vital cogs in the Holy See’s global machine, this is a top-down hierarchy. While Gallagher insists that there is a continuity to the Vatican’s approach to international affairs, led by the teachings of the Gospel, his department must “reflect the priorities of the pope of the day”. Where Francis is concerned this means a relentless pursuit of opportunities for peacemaking. It’s a stance that’s led to comparisons with John Paul II, who is credited with ushering in the fall of communism. “He is a communicator like John Paul II,” says Francis Rooney, a former US ambassador to the Holy See and author of The Global Vatican. “Except now we have an Argentine pope dealing with issues such as Islamic extremism. Then we saw a Polish cardinal, whom the KGB had pursued his whole life, speaking out against a regime he despised.”

Vatican diplomacy goes beyond the welfare of Catholics or even Christians. Its reach is reflected by the spread of foreign missions accredited to the Holy See: Egypt’s large embassy is just yards from the entrance of the Secretariat and Iran has one of the largest number of accredited diplomats.

It seems odd that so many non-Christian countries are so well staffed here. “Often a religious country – and that might be Islamic or any other faith – might understand the power and relevance of the Holy See even more than that of a western secular government,” says Nigel Baker, the British ambassador who meets MONOCLE in his residence.

In turn, Pope Francis has made no secret of his desire to seek reconciliation in the Middle East. “We’re interacting with most of the principal countries involved in the Syrian crisis,” adds Gallagher who insists the Middle East’s web of interconnecting conflicts is high on the papal agenda. “Our role – which I think is profoundly religious and spiritual – is to appeal to all men and women of good will, to national leaders, to make every effort – enormous efforts – to try and break through this most complex of conflicts. We have a sense of urgency.”

The Holy See has a powerful and unique diplomatic platform. Unlike a conventional sovereign state, there is no national interest to protect, no commercial assets to promote and no expeditionary military force to use as leverage. Talking really is its main tool. It has the status and profile of the pope to trumpet its values. And of course there’s faith. Baker insists the Holy See should be viewed as a global network, rather than just the small sovereign enclave that surrounds St Peter’s. (He compares his post to that of a multilateral institution such as the osce or the UN.) “The Vatican City state is a part of the global Holy See network: 5,000 bishops, 400,000 priests, more than 1.2 billion Catholics. It is both global and local.”

It’s precisely this vast scope that leaves the Vatican’s foreign-affairs image vulnerable. “To some extent the pope is limited by the global hierarchy of the Holy See,” says Philip Seib, professor of public diplomacy at the University of Southern California. “There are a lot of people within its political infrastructure who are very, very far to the right of him, and there’s not a lot he can do about it.”

Seib cites the media storm that erupted during Pope Francis’s recent trip to the US when it emerged he had given an audience to Kim Davis, a county clerk who had been jailed for refusing to issue marriage licences to same-sex couples. “She had been invited by the Washington nuncio,” says Seib. “All the good public diplomacy that was done previous to that was severely hurt by that incident.”

On issues of pure foreign policy the Holy See has clearer doctrine. The Vatican is openly against any military solutions unless they meet the conditions of a “just war” laid down by Catholic tradition. In many ways this stance leaves the church as one of the biggest advocates of diplomacy. “We’ve seen that many great things can be achieved,” says Gallagher. “If you take the P5+1 breakthrough on the nuclear question in Iran, well, a lot of people years ago would have said that’s not possible. We welcome that. These sort of things are possible via diplomatic dialogue and discussion.”

Whether religious or not, the world’s leaders are keen to engage Francis. It’s clear his interventions have the power to make politicians think about the right thing to do. Whether it’s the tableau of Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas and Israeli president Shimon Peres praying together in Rome (as they did in 2014) or Pope Francis’s little Fiat flanked by a convoy of huge, armoured SUVs, his methods are effective and unconventional. “He is a pope of surprises who believes in the God of surprises,” says Gallagher. “He has the courage to think outside the box and there are a lot of us who think, ‘Why shouldn’t I go that extra mile with him?’”

To find out more about the Vatican’s foreign ministry, watch our film.

Fighting talk

In November 2015, Pope Francis became the first pontiff in modern history to visit an active war zone. He spent 24 hours in the Central African Republic, where a civil war between a Muslim minority and a Christian majority has been raging since March 2013. At the Saint Sauveur camp for displaced people in Bangui he led the crowd in a chant of “We are all brothers”. “I wish for you and all Central Africans a great peace... whatever may be your ethnicity, your religion, your social status,” he said. He also visited Koudoukou central mosque in an area where 15,000 Muslims were surrounded by armed Christian militias. There he bowed to Mecca and said, “God is peace, salaam.”

Almight fallout

The Vatican’s hands-on approach to foreign affairs has some critics. One Washington-based group, Catholics for Choice, has been campaigning to demote the Holy See from its permanent-observer status at the UN. “The reality is that when people are negotiating issues regarding sexual and reproductive health, the Holy See takes an outmoded view. They can be very obstructionist,” says Jon O’Brien, the organisation’s president. “Many people laud Pope Francis for having a pastoral approach but the reality is he has left cardinals and bishops to proceed as normal. He’s not changed the game plan that was in place with the previous two popes; they appointed hard-core, conservative diplomats. They are still trying to block people getting access to what they need. The reality is that poor people die without access to contraception.”