Thirty-three years ago on August 9, 1974, President Richard Nixon resigned the presidency. His name is mostly associated with Watergate scandal. Putting aside all details and controversy regarding Nixon’s politics — all that...

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

Rebuilding Trust with Russia Through Science Diplomacy

The relationship between Russia and Western democratic countries—the U.S. and the UK in particular—in the twenty-first century might be characterized by mistrust. Mistrust is rooted in Russia’s recent foreign policy approaches to Syria and Ukraine and in other serious issues related to its possible meddling in the 2016 American presidential elections or the Skripals’ poisoning on British soil in March 2018.

Subsequent sanctions on Russia, economic pressure and the escalation of the diplomatic tensions with the U.S. and the UK make Russia even more estranged from the international community, making it even more proactive in reshaping geopolitical configurations to suit its own view. Alternatively, the U.S. and the UK might consider implementing approaches of public and science diplomacy in dealings with Russia. One may argue that this exchange might not be on the same level as Russia’s misbehavior, yet the soft power of public diplomacy and the cohesive power of science diplomacy have long-term outcomes and great potential to rebuild trust and normalize inter-state relations as a means of goodwill and well-being.

Public diplomacy has various implications, considering a country’s wide range of possibilities to generate soft power of attraction and cooperation through educational, cultural or sports diplomacy, as well as maintaining strategic communication and engagement with audiences to promote healthy inter-state relations. Public diplomacy also suggests future-oriented forms in international relations that could be beneficial not only to the U.S., the UK and Russia but other countries and includes an agenda for attracting various non-state actors via people-to-people interactions.

Science diplomacy has slightly different characteristics and approaches. There is sustained, shared regulation and continuous supervision of global issues through international treaties and declarations, e.g., the Arctic Council, the Antarctic Treaty, and the Non-Proliferation Treaty.

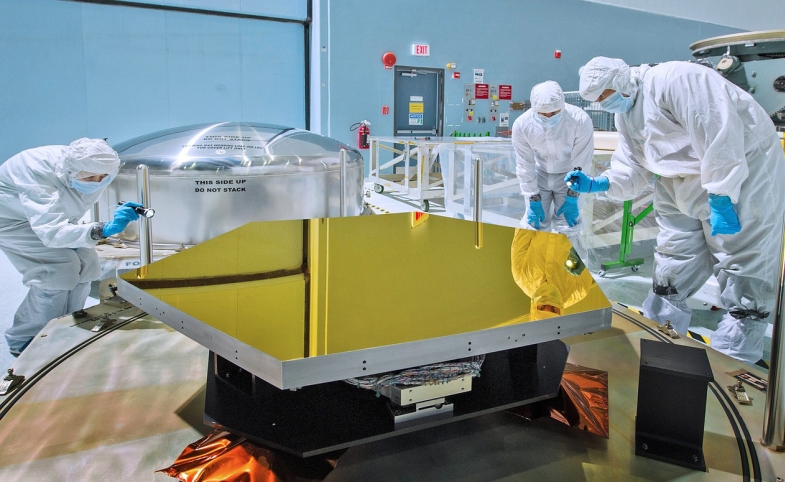

Using science diplomacy is also beneficial in improving bilateral relations when official relations are uneasy or limited. Science diplomacy is perceived to be a visionary way of keeping the door open for current negotiations that potentially paves the way to restoring trust and improving Russia’s damaged image as an attractive and cooperative country. Plus, Russia is still a permanent member of the UN Security Council and plays an important role in international scientific cooperation, including in the space program and in the facilitation of work and research on the International Space Station.

Science diplomacy also has its distinct characteristics and is related to a state’s ability to grow its influence internationally, including the power to change geopolitical configurations. The U.S. and the UK, who are trendsetters in science diplomacy, understand the meaning and value when science diplomacy is properly implemented into a state’s foreign policy. Russia, however, lacks the ability to generate science diplomacy now but has greater experience in its usage. For instance, in the Cold War, the two contrasting superpowers of the U.S. and the Soviet Union were able to cooperate on scientific matters.

Engaging with Russia instead of driving a wedge between them should be the policy of the U.S. and the UK.

The emphasis on science diplomacy might be a bargaining chip in dealings with Russia, as it fits well with the controversial image of a country that struggles to put forward positive stories but dreams of its past influence. Science diplomacy might come together with a public diplomacy approach to engage with international audiences and show that Russia’s diplomacy is a part of the universal diplomatic culture and that its scientific culture goes along with perceptions of the universalism of science.

As Geoffrey Wiseman noted in his recent conference paper, there is considerable evidence to support the idea that there is both a universal (or an international society-based) diplomatic culture as well as national diplomatic cultures. Extending this statement, it may be suggested that science diplomacy approaches are universal but have distinct national characteristics that are derived from community standards, historical and cultural backgrounds, and institutional structures.

So, what are the differences that Russia’s science diplomacy might have beyond the accepted universality of diplomatic culture and science? What can be taken into account to understand Russia’s science diplomacy better, to negotiate more efficiently, and to eventually reduce diplomatic tensions and improve relations?

Russian diplomacy standards are taken from the European style and go back to the early 18th century when Peter the Great reformed the state system and adapted the European diplomatic model. At the same time, Russian diplomatic style refers to a regional component of state sovereignty and the eradication of any temptation to interfere in its internal affairs.

Science in Russia is similar to that in Britain and France, as the Russian scientific community was part of the European community. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union’s experience and expertise in space technologies, together with its fundamental research and expansion of its nuclear and atomic weapons technology, were profound and helped build a strong industrial and military profile to ensure its position as a superpower. The national components refer to the cohesive hard power of military and scientific capability that contributed to Soviet science diplomacy; however, uneven scientific development bestowed national pride on some scientific achievements while acknowledging total inferiority in others. Russia’s style in science diplomacy may be characterized as rational based on hard power, although it lacks the soft power of attraction.

Acknowledging differences on the national and regional level helps to develop diplomatic negotiations, whether bilaterally or multilaterally, while neglecting national or regional differences that might remain obstacles to building inter-state relations. Engaging with Russia instead of driving a wedge between them should be the policy of the U.S. and the UK, as these countries are perceived to be more comprehensive, sensible and transparent major powers. Otherwise, Russia’s continued isolation strengthens Putin’s regime domestically and overshadows liberal hopes of building a democratic state there any time soon. Undemocratic Russia might be a threat not only to the democratic world but also to itself, corroding its institutions and organizations from within.

Science diplomacy should be a priority for Western democracies in engaging with Russia and using the persuasive power of public diplomacy to create a certain narrative. If implemented properly, science and public diplomacy together will lead to the future normalization of relations with Russia, promotion of democracy and shared values of liberalism, and ultimately address global issues in the reality of a multi-polar world.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

February 6

-

January 8

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.