This photo essay on hip-hop diplomacy depicts the first Next Level program in India that recently came to a close after a three-week tour in Patna and Kolkata... The Next Level program, sponsored by the U.S....

KEEP READINGThe CPD Blog is intended to stimulate dialog among scholars and practitioners from around the world in the public diplomacy sphere. The opinions represented here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect CPD's views. For blogger guidelines, click here.

Jazz Ambassadors: An Instrument of Public Diplomacy

Jazz, as a cultural phenomenon, can comprehensively illustrate U.S. culture and society. As a component of U.S. public diplomacy, it can reasonably tell an American story to foreign audiences. Since 1956, after the U.S. State Department created the Jazz Ambassadors program, jazz diplomacy not only defined the success of U.S. public diplomacy in the Cold War, but became one of the universal symbols of the United States in the country of Georgia, a Soviet Republic at that time. Until 1978, before the U.S. State Department directed this jazzy instrument of public diplomacy, Georgians experienced the American value of freedom through jazz rhythms.

Soviet socialist realism forbade everything Western, especially American, including freedom of pro-Western thinking, and freedom of experiencing U.S. values. Soviet ideology regarded American jazz as “corrupt” and “dissident.” In this case, only high-level political agreements between the United States and the Soviet Union authorized American jazz concerts in Soviet cities.

Classic American jazz became a counterpoint to Soviet propaganda for Georgians.

However, Soviet propaganda about American jazz did not influence Georgians, who embraced the value of freedom through American jazz during the Cold War. Every evening, many Georgians, who were tired of Soviet propaganda, were secretly listening to Voice of America (VOA)'s Willis Conover “Jazz Hour” behind closed windows and doors. Additionally, because the Soviets were jamming to VOA on radios made in the Soviet Union and they did not have special receivers to get the VOA signal, Georgians were even crafting additional radio parts at home so they could listen to Conover’s program and relax from Soviet reality.

The first phase of U.S. jazz diplomacy began in 1962 after the U.S. Congress passed the Fulbright-Hays Act of 1961, officially known as the Mutual Educational and Cultural Exchange Act. As a part of this exchange agreement, the first U.S. Jazz Ambassador Benny Goodman, along with Joya Sherrill, visited Tbilisi, the capital city of Georgia. His five concerts in Tbilisi in 1962 were attended by thousands of Georgians. In addition to performing classic jazz compositions, Goodman was improvising and even invited two Georgian drummers on the stage during one of his concerts. At these concerts, no contact between jazz ambassadors and their fans was allowed, and Soviet leadership strictly controlled every aspect of the jazz ambassadors’ tours. Goodman reaching out to his audience was a brave act, showing that jazz can connect people.

Benny Goodman and Joya Sherrill performing in Tbilisi from the newspaper, Communist, June 10, 1962. Image provided by the author.

One interesting case that became a visible example of Georgians’ rejection of Soviet ideology occurred at one of Goodman’s concerts in Tbilisi when Sherrill performed a Russian-language Soviet folk song, “Katyusha.” The Georgian audience hooted its disapproval because it did not like her singing a Russian song in Tbilisi. Sherrill washed away Georgians’ feelings of disappointment in a diplomatic manner: she performed pure American jazz songs at a concert the following day.

The second phase of U.S. jazz diplomacy in Georgia was initiated in 1966 after a new agreement between the U.S. and the USSR titled, “Exchanges in the Scientific, Technical, Educational, Cultural and Other Fields.” The second jazz ambassador visiting Tbilisi was Earl Hines, along with Clea Bradford. Hines was deeply aware of the potential of jazz to link people, and he supported more jazz tours to break down Cold War barriers between peoples. Several of Hines’ concerts in large cities were cancelled by Soviet leadership, presumably because of the Vietnam War or because officials did not want jazz to be popular in big Soviet cities.

Cartoon of Earl Hines by cartoonist Gigla Pirtskhalava from the newspaper, Tbilisi, July 20, 1966. Image provided by the author.

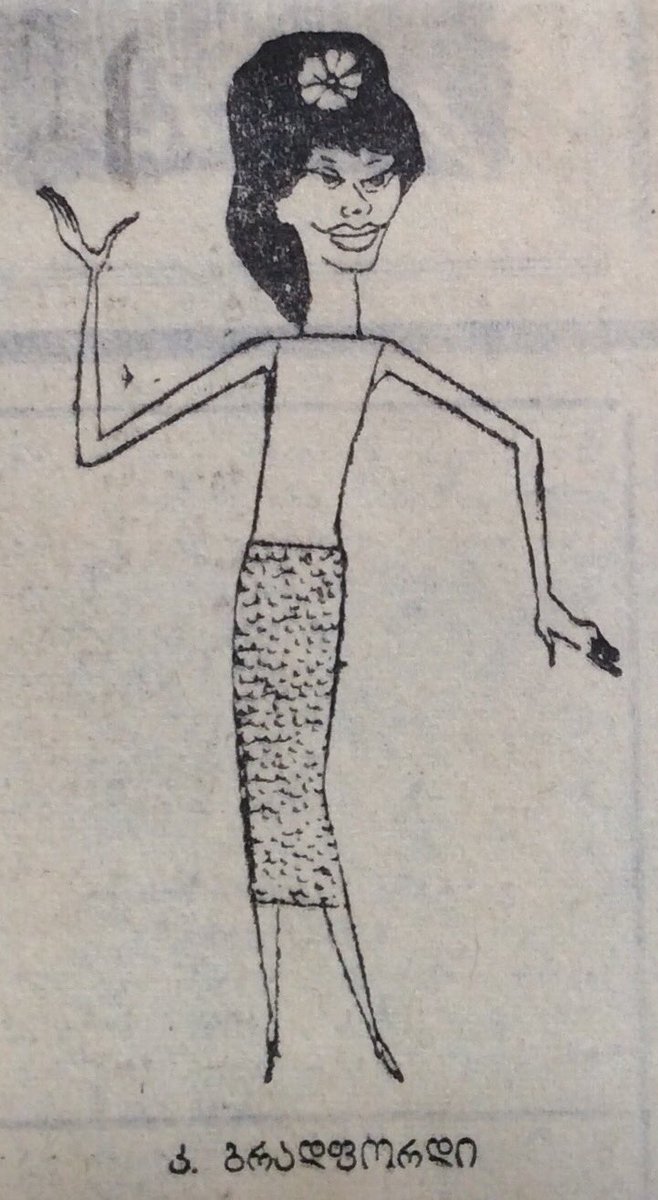

Cartoon of Clea Bradford by cartoonist Gigla Pirtskhalava from the newspaper, Tbilisi, July 20, 1966. Image provided by the author.

Benny Goodman’s jazz tour opened the door to more Western jazz in Soviet Tbilisi, while the Earl Hines' concerts indicated that the day when Georgians could freely listen to jazz music would come soon. And it did. In the 1970s, Soviet leadership liberalized its policies about jazz, and a new agreement on exchange programs was signed by the U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union Jacob D. Beam and Deputy Foreign Minister of the Soviet Union Andrei A. Smirnov. By this time, jazz could be more freely experienced. Therefore, when Thad Jones, the Mel Lewis Band and Dee Dee Bridgewater came to Georgia in 1972, their concerts did not have the same dramatic impact of the first two jazz ambassadors in Tbilisi.

All these phases of the U.S. jazz diplomacy programs helped calm the tense atmosphere in Georgia that had been created by Cold War politics. Classic American jazz became a counterpoint to Soviet propaganda for Georgians. It deepened the feeling of freedom—a value shared by Americans and Georgians—and proved that jazz ambassadors can make jazz diplomacy an instrument of public diplomacy.

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

POPULAR ARTICLES

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

February 6

-

January 28

Join the Conversation

Interested in contributing to the CPD Blog? We welcome your posts. Read our guidelines and find out how you can submit blogs and photo essays >.