India Inside Out - A Case Study in Indian Public Diplomacy

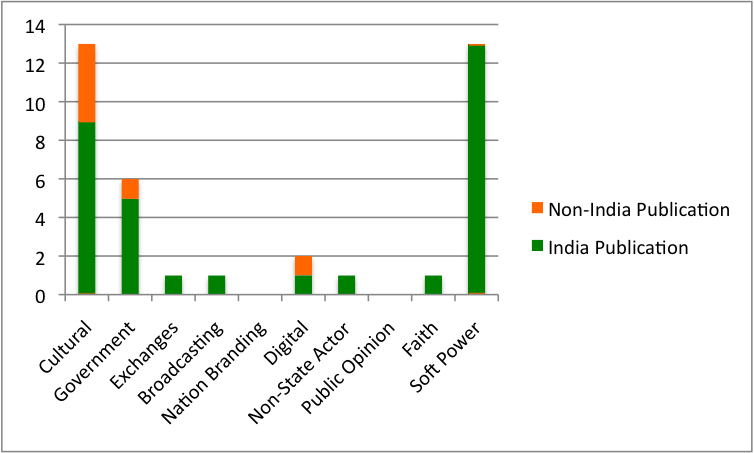

Articles on Indian public diplomacy - from Indian and non-Indian publications

In November 2010, President Obama said on his inaugural visit to New Delhi, “India is not simply emerging, it has emerged.” In many ways, of course, this is true. India endured the economic collapse with resiliency, hovering between seven and nine percent GDP growth in 2011; it is speculated that the country has a chance at permanent-member status on the United Nations Security Council; and with its young population, India is perfectly poised on a trajectory to world leadership. On the other hand, India still lags behind on several key human development indices, ranking 134 of 187 in the most recent UN report, a challenge compounded by rapid urbanization.

For all these reasons and complexities—and a few more—India makes for a fascinating case study in public diplomacy, and in December 2011, six of my colleagues and I journeyed to New Delhi, Vishakapatnam, and Mumbai with the goal of appraising India’s public diplomacy strategy. Over the course of two weeks, we met with Indian government and civil society leaders, explored the culture, and experienced the sights, sounds, and smells of two of India’s largest cities. And along the way, we shared our conversations with people from around the world through the website, www.IndiaPublicDiplomacy.com. Our key deliverable was a report that summarized our findings in six key areas: government public diplomacy, development, urbanization, citizen diplomacy, media, and Indo-Arab relations. The report will be available publicly in the coming weeks.

In approaching this project, my core question was one that required reconciliation, rather than an answer. How can India boast such high levels of economic growth, yet sustain some of the worst rates of child malnutrition, poverty, and gender inequity in the developing world? It’s a question that media coverage of India is beginning to ask: is India’s rise as a “new world power” both true and a “false reality”? Development was a key research area for us, and yielded a clear finding: Indians are hands-on when it comes to addressing the development challenges the country faces. They are engaged and invested in their own development, and this message was palpable in our conversations with a host of NGOs, social justice activists, and graduate students. Yet these groups may not be representative of all Indians; one of our Indian interviewees proposed that Indians’ “cultural tolerance of inequality is tremendous.”

Thus, while we found that India has a robust civil society that in many ways is filling in the gaps that the government cannot due to a shortage of manpower, the Government of India could be doing much more to engage its own citizens in development, and for that matter, in public diplomacy.

By seeing a large population as an opportunity—a strength to be leveraged—India would achieve both its internal and external public diplomacy objectives. In our conversation with Anita Rajan, who is a part of the office that advises the Prime Minister on the National Council on Skill Development (NCSD), she described India as being “on the brink,” and ready to excel in the next decade, provided that India’s youth population is equipped with the right skills. NCSD uses a public-private partnership model to provide vocational training, with the goal of skilling 500 million people by 2022, and these partnerships, it became clear, are paramount in enabling large-scale change.

We found that many Indians unknowingly act as citizen diplomats; take, for example, the leadership team at Women in Security, Conflict Management and Peace (WISCOMP), an organization that trains women community leaders—from entrepreneurs to lawyers—in conflict transformation. They take on the challenging process of tough relationships like Kashmir and Pakistan: areas many people cast aside as too touchy. One aspect of their programs is facilitating dialogue between these women leaders, the military, and government bureaucrats. WISCOMP’s approach is another model that can be replicated, and the more these types of collaborations happen, the closer India comes to achieving its public diplomacy objectives.

One challenge the Government of India will face along the way is the diluted citizen trust in its activities. A recent Times of India poll found that 60% of Indians feel that corruption is the country’s biggest weakness, up nearly 20% from a Hindu Times poll conducted in February 2011. This is a critical problem because if India is perceived as corrupt on international indices as well as amongst its own people, then her credibility is damaged, and her ability to conduct public diplomacy is diminished, if not demolished. The government gets this, as evidenced by the comprehensive e-governance plan produced under the leadership of Abhishek Singh in the Ministry of Communications & Information Technology. India’s e-governance initiatives are promising on two fronts: first, the plan is accelerating the rate at which rural India becomes Internet-connected, and further accelerates the debate India must now face over Internet freedom; second, India’s expertise in e-governance creates an opportunity to share its expertise with other countries facing similar issues.

India’s relationship with the Arab world was an interesting case study for understanding the country’s foreign relations, and where public diplomacy fits in—or doesn’t. On the surface, Indo-Arab relations can be characterized as a strong business partnership. Given the many cultural and religious ties and a large Indian diaspora community in many Gulf countries, not expanding on this is a missed opportunity. But what is more promising, and more quietly pursued, is India’s engagement with countries working to re-build their governments post-revolution; here, India can offer its expertise as the world’s largest democracy, which will perhaps be more warmly welcomed than the American variety.

It became clear to us that India has much to offer the world besides its economic prowess. Indians’ work towards solving their country’s challenges is promising; the next step for India is in leveraging both the work of government and Indian civil society to do international knowledge sharing and capacity building. In doing so, India will rightly find its role in world leadership.

Tags

Issue Contents

Most Read CPD Blogs

-

January 29

-

January 20

-

January 28

-

February 6

-

January 28

Visit CPD's Online Library

Explore CPD's vast online database featuring the latest books, articles, speeches and information on international organizations dedicated to public diplomacy.

Add comment